In Little Nightmares II, the world of The Pale City stands as a decayed monument to a society swallowed by media control. Unlike the claustrophobic oppression of The Maw from the first game, this sequel expands outward—both physically and thematically—to explore the manipulation of reality through screens, signals, and psychological dependence. At the heart of it all lies the mysterious Transmission Tower, a structure that broadcasts more than noise; it projects obedience, distraction, and submission.

This article dives deeply into the symbolism of media manipulation in Little Nightmares II—examining how every distorted television, every flickering image, and every humming static pulse contributes to the game’s portrayal of control through perception. Organized in ten chronological sections, this analysis will trace the journey from Mono’s early encounters with the televisions to the Tower’s final revelation, unpacking how the environment, enemies, and narrative collectively portray the disintegration of individual will under mass influence.

The Static Beginning: The Transmission’s First Whisper

From the opening scene, Little Nightmares II uses static as a language. Mono awakens in a forest drenched in electronic hum—a place where nature and machine already coexist uneasily. The faint television noise echoes across the trees, setting the tone for a world infected by invisible frequencies.

The forest functions as the game’s psychological primer. It isolates the player before immersing them in media distortion. The scattered televisions here are not yet active tools of control, but relics of a forgotten obsession. They hint at a civilization once addicted to images, now consumed by their residue.

The moment Mono touches a TV and is drawn inside it marks the birth of connection. His ability to travel through screens foreshadows the dual nature of media: liberation and enslavement. The static calls to him like a siren, promising meaning while stealing autonomy.

The Hunter’s Cabin: Domestic Surveillance and Paranoia

The Hunter’s Cabin is the first enclosed environment where the themes of control manifest spatially. Its layout is suffocating—walls lined with mounted trophies, tools, and taxidermied creatures. Every surface feels watched. Even without technology, this space embodies surveillance; the Hunter’s gaze is everywhere.

When Mono and Six encounter the television in the basement, it acts as a silent observer, a cold eye that replaces human presence. In a world devoid of dialogue, the TV becomes the only voice—a symbol of how communication can be monopolized by a single source.

The Hunter’s domain mirrors the paranoia of a society that monitors and collects. His obsession with preserving what he kills echoes the way media freezes life into consumable fragments. The Cabin thus becomes an early metaphor for the first stage of manipulation: possession through observation.

The City Streets: Descent into the Broadcast

Upon escaping the forest, Mono and Six enter The Pale City, where the architecture itself becomes enslaved by television. Skyscrapers lean under the weight of antennas, wires snake across alleys, and the sky glows with static haze. Every building is both home and receiver, feeding from the Tower’s unseen frequency.

The citizens—now known as Viewers—are the living proof of total control. They are not monsters in the traditional sense, but victims so captivated by the broadcast that they’ve become extensions of it. Their motionless bodies and hollow faces are a chilling visualization of passive consumption.

Here, Little Nightmares II transitions from personal horror to societal commentary. The city doesn’t just represent a dystopia—it reveals what happens when reality is replaced by projection. Each television in the street acts as both a doorway and a mirror, reflecting humanity’s dependence on its own illusions.

The School: Indoctrination and the Architecture of Obedience

The next stage of Mono’s journey takes him into the School—an environment that embodies institutional control. The setting’s design, filled with identical desks, harsh lighting, and towering walls, communicates the suppression of individuality. The Teacher’s monstrous neck allows her to surveil from every angle, enforcing discipline even in absence.

The symbolism here is direct yet profound: education turned indoctrination. The students, who mimic obedience through grotesque physicality, illustrate the long-term effects of a system built on conformity. Their clay faces and uniform actions echo the emotional numbness of mass programming.

In this environment, television’s influence is subtler but pervasive. Posters, classroom arrangements, and even sound design mimic rhythmic patterns of control. The School teaches not curiosity, but obedience—preparing its subjects to become the passive Viewers seen later in the city.

The Hospital: Disembodiment and the Mechanization of Humanity

The Hospital marks a descent into a different kind of manipulation—the technological obsession with control over the human body. Television light flickers across hallways filled with prosthetics, x-rays, and lifeless limbs. Here, screens are medical tools, symbols of authority and surveillance dressed as healing.

The Doctor’s monstrous mobility—crawling along the ceiling like a spider—represents the inversion of trust. The very institutions designed to protect life have become instruments of domination. Patients are no longer treated, but modified, molded into silent compliance.

The flickering televisions in this section serve as anesthetics, numbing awareness. They distract both characters and players, lulling them into momentary comfort before horror strikes. The Hospital teaches that control is not always overt; it thrives under the illusion of care.

The Signal Tower’s Influence: The Invisible Master

As Mono progresses through The Pale City, the Transmission Tower’s reach becomes increasingly apparent. Static interrupts reality itself—distorting walls, bending hallways, and altering gravity. It’s as if the city no longer obeys physics, but the signal’s emotional logic.

The Tower symbolizes centralization of power. Its faceless presence dominates the skyline, representing the unseen authority behind all manipulation. The humming resonance in every corner of the city is its heartbeat—a reminder that even silence is manufactured.

By the time Mono reaches the outer gates, the player has internalized this control. The televisions no longer feel foreign; they are tools, gateways, even allies. This psychological conditioning parallels real-world dependence on media, where instruments of control are mistaken for comfort.

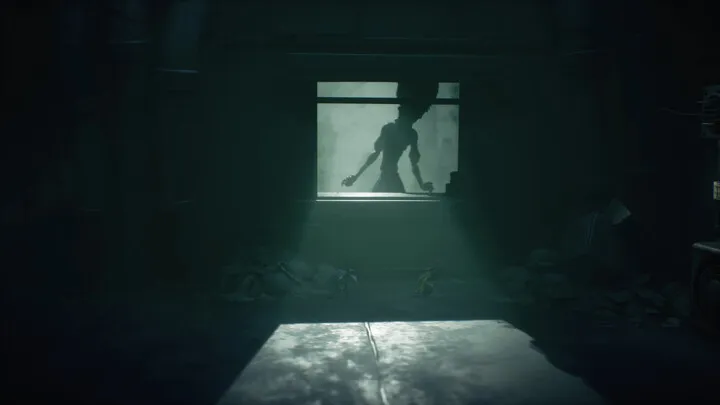

The Thin Man: The Embodiment of Transmission

The Thin Man is the game’s most direct manifestation of the Tower’s influence. He emerges from televisions like a living broadcast, his every movement stretched and distorted by static. Unlike previous enemies, he doesn’t chase blindly—he pursues with purpose, like a signal honing in on its receiver.

His design encapsulates depersonalized power: suit, hat, and no identity. He is the image of authority stripped of humanity. The Thin Man represents not a person, but the act of broadcasting itself—the endless repetition of control through endless screens.

When Mono confronts and eventually overcomes him, it’s not just a battle between two figures; it’s a collision between transmitter and receiver. Yet victory comes at a cost—Mono inherits the role. The cycle continues, suggesting that those who resist control can easily become its next vessel.

The Tower’s Core: Spatial Distortion as Symbolic Collapse

The final journey into the Tower blurs all boundaries between reality and transmission. The architecture folds in on itself, creating looping corridors and impossible geometries. This collapse of space mirrors the disintegration of truth in a world consumed by signal.

The interior aesthetic—liquid walls, floating debris, pulsating static—evokes both awe and nausea. It’s the visual language of control taken to its extreme, where even perception cannot be trusted. The Tower doesn’t just manipulate; it redefines existence.

Thematically, this represents the ultimate consequence of media domination: the erasure of difference between subject and signal. Mono’s gradual absorption into the environment confirms the total victory of manipulation. The final act becomes an allegory for surrendering identity to collective illusion.

The Betrayal and Transformation: Mono as the Next Transmitter

The climactic betrayal by Six is one of the most emotionally charged moments in the series. Yet it’s not just personal—it’s thematic. By letting Mono fall, Six symbolically severs the human connection that could have broken the cycle. In isolation, Mono becomes susceptible to the very force he once resisted.

The transformation sequence that follows, where Mono evolves into the Thin Man, completes the tragic loop. His body stretches, his face disappears, and his humanity is absorbed by static. The Tower gains a new transmitter, born from despair.

This ending crystallizes the game’s message: control perpetuates itself through trauma and loss. Every rebellion feeds the next generation of manipulation. The system doesn’t need to destroy its enemies—it only needs to transform them.

The Meaning of Control: What Little Nightmares II Says About Us

In Little Nightmares II, the Transmission Tower is more than a plot device; it is a mirror held up to our age of screens and noise. The game’s horror stems from recognition—the realization that its world is not fantasy, but metaphor. We too live amidst signals that shape perception and desire.

By using silence, distortion, and surreal architecture, the game captures the emotional texture of living under constant influence. It doesn’t preach or moralize; it immerses. Each flickering screen is both warning and reflection—a reminder that control today comes not from chains, but from attention.

Ultimately, the brilliance of Little Nightmares II lies in its quiet critique. It shows us that manipulation doesn’t shout; it hums softly in the background, comforting and hypnotic. And in that comfort, we lose ourselves.

Conclusion

The story of Little Nightmares II is not just about fear—it’s about the surrender of self to systems too vast to comprehend. Through its haunting depiction of media control, the game constructs an atmosphere where screens are both doors and prisons, where information becomes addiction, and where the act of watching slowly consumes the watcher.

From Mono’s first encounter with the static to his final metamorphosis, every frame of Little Nightmares II tells a story of perception twisted into obedience. The game asks a chilling question: when reality itself becomes a broadcast, who among us is truly awake?